Part III: A Change of Plan

By Marc Edge

By Marc Edge

If I had any doubts about why I sailed away to the tropics, they were dispelled back in Vancouver. The temperature was below freezing when I arrived, and then went down to 10 below. Then it warmed up enough to dump a record snowfall on the city. I was actually glad to get back to Tonga. The only problem there was that it was then not only cyclone season, but also rainy season as well as the height of summer. I had brought back with me some gear to install, but doing any work below decks was almost impossible because of the blinding sweat any exertion would bring. About the only way to stay cool was to find some shade under the cockpit awning, drink cold beverages, stay still and read. Luckily, I'd also brought back a pile of books to read. In addition, I had acquired the charts and guide books needed to continue my voyage westward through Fiji, Vanuatu and New Caledonia to Australia. Maybe there I could find newspaper work and stay long enough to replenish my cruising kitty and find crew to sail up to Indonesia and across the Indian Ocean to South Africa. But I was of two minds, having just about had my fill of cruising with recalcitrant crew. While my water pump was being repaired in September, I had set about applying to several doctoral programs in the U.S. I had done some research into the matter while in San Diego and ordered information from a dozen or so universities, which caught up to me at mail drops along the way. With time on my hands while crewless in Tonga, I had decided to apply to Indiana and Michigan State, where I had done my Master's degree. I wanted to apply to three schools, but was undecided on a third. Finally, I decided on Ohio University, which I had not heard of before, but which was attractive because it was on the quarter system instead of semesters like the others. I would end up taking more courses, which I thought was a good idea because I had never really studied Mass Communication before, despite having been a journalist for more than 20 years. Ohio operated year-round also, so I could start in the summer, when I would not be teaching but had my tuition paid by scholarship. I wasn't sure if going back to school and embarking on a second career of teaching was what I really wanted to do. After all, it had been 15 years since I had been in school. Starting in the summer without the pressure of teaching for the first time seemed like a good idea to me.

Beginning after my return in the New Year, I had intermittent contact with the three universities by fax, which is an extremely problematic way to communicate in Vavau due to the antiquated phone lines, which are linked to the satellite dish in Tongatapu by radio. Michigan State was very keen on having a journalist with 20 years of experience as a teaching assistant, and offered a stipend of about $10,000US for two semesters. The scholarship they offered, would only cover two courses, and I would have to pay extra to take a third or fourth course. Ohio, which offered the same teaching assistantship but paid for a full course load of 18 credit hours. I asked if they would match the $1,000 in moving expenses Michigan State was offering, and they responded that as I was their top candidate they would make an exception and do so. I finally got a response out of Indiana, which did not intend on making admission decisions until March, so by mid-February, I had decided to attend Ohio University. But where on earth was Athens, Ohio? Somewhere in Ohio, I reasoned, and made plans to sail north to Samoa and Hawaii instead of west to Fiji and Australia. My next problem was, of course, crew. Joyce on the next boat from me, Energetic, was having to leave Tonga because her six month visa was expiring. If she left, she could return and get another six months, and she knew a single-hander in Pago Pago who needed crew to Tonga, so she was interested in catching a ride up there. I contacted my friend Ian, who had sailed with me back home and was very handy as a mechanic, and he was interested in sailing the South Pacific. I knew it was much less expensive to fly to American Samoa from the U.S. than to Tonga from almost anywhere, so I suggested he meet us there and set about looking for another crew member in Neiafu. And then along came Oscar.

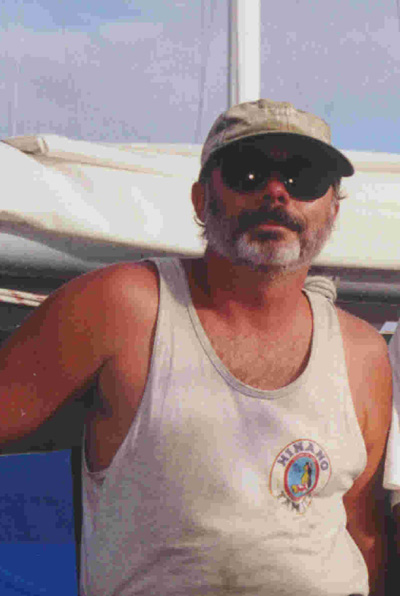

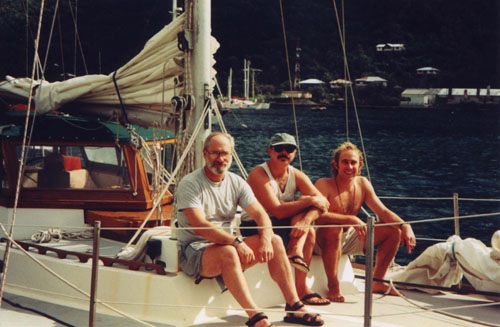

Early March is a bit soon to be sailing from New Zealand to Tonga, but the Moorings charter company needed a new Beneteau delivered in time for high season, and Oscar had signed on as crew. A Canadian by birth and an accountant by profession, Oscar had been traveling in Asia since quitting the job as an economist for seven years he had held for seven years in London, England. He wanted to return to Canada, having grown up in Ontario, and was interested in moving to Vancouver. I mentioned I was sailing there and might need somebody to botanist Markenurh while I was off at school, and he was interested. Together the three of us set off on April 10, north to Samoa to meet Ian.

Doing the Macarena in Pago Pago

Almost as soon as we left Tonga, the mechanical problems

began. We motored for awhile because the winds were light, and when

we had enough wind we raised sail and turned off the engine. Before too

long, however, the wind dropped again and we decided to turn on the engine

again. There was only one problem -- the engine wouldn't even turn over.

Joyce said she thought she knew what the problem was because they'd had

a similar problem on Energetic a sticky solenoid failing to provide

power to the starter. We were bobbing around pretty well now in a glassy

sea, and the tropical heat was stifling, but I wedged myself into the engine

room to remove said solenoid. It seemed loose enough to me, so I put it

back together. We turned the ignition key again. Still nothing. We tried

various things, but the problem was obviously beyond the collective expertise

of the three of us. So we waited. And waited. And waited for the wind to

come back. The sails slatted around until we got tired of listening to

them and took them down. And we rolled. And rolled. Finally, after a few

days, the wind came back. Gradually at first, but soon we were doing a

couple of knots, and when we hit three knots I'll swear we were flying!

Finally, the cloud-covered peak of Pago Pago hove into view. Joyce got

on the VHF radio and called to some boats she knew in the harbor and they

offered to meet us at the harbor entrance with dinghies to help us in.

Almost as soon as we left Tonga, the mechanical problems

began. We motored for awhile because the winds were light, and when

we had enough wind we raised sail and turned off the engine. Before too

long, however, the wind dropped again and we decided to turn on the engine

again. There was only one problem -- the engine wouldn't even turn over.

Joyce said she thought she knew what the problem was because they'd had

a similar problem on Energetic a sticky solenoid failing to provide

power to the starter. We were bobbing around pretty well now in a glassy

sea, and the tropical heat was stifling, but I wedged myself into the engine

room to remove said solenoid. It seemed loose enough to me, so I put it

back together. We turned the ignition key again. Still nothing. We tried

various things, but the problem was obviously beyond the collective expertise

of the three of us. So we waited. And waited. And waited for the wind to

come back. The sails slatted around until we got tired of listening to

them and took them down. And we rolled. And rolled. Finally, after a few

days, the wind came back. Gradually at first, but soon we were doing a

couple of knots, and when we hit three knots I'll swear we were flying!

Finally, the cloud-covered peak of Pago Pago hove into view. Joyce got

on the VHF radio and called to some boats she knew in the harbor and they

offered to meet us at the harbor entrance with dinghies to help us in.

It was mid-day by the time we got to the entrance, but our docking under dinghy tow provided to be our first lesson in the Pago lifestyle. Frank, who was driving one of the dinghies, was drunk already and proved a bit over-zealous on approach, resulting in a hard landing and major dent in Markenurh 's hull. We soon learned that early inebriation is an endemic condition locally due to both the cheap availability of liquor and lack of other, healthier diversions. But, we had arrived. Our timing, as usual, was perfect. We had been told by several cruisers in Tonga to make sure we didn't arrive in Pago on their national holiday, on which they celebrate their association with the U.S. -- sort of a Dependence Day. Of course, what was the day after we arrived but the national holiday. By 5 a.m. the dock was lined with hundreds of Samoans waiting to see the canoe races. We had a ringside seat, but having that kind of crowd around the boat made us understandably nervous. Luckily, a security guard, sent by an authority unknown, was one of the first to arrive, and the rest of the throng stayed off the boat as a result.

We couldn't stay at the customs dock for long, however, but I explained to the port captain that my mechanic was flying in on the plane arriving the next night and we would soon have our engine problem fixed. While we were at the dock, however, we decided to fill up with diesel and water and took advantage of the fuel truck's presence at a nearby boat to fill our own tank. Oscar offered to fill the water tank, and I agreed, being already on my third beer. Usually I watch the crew carefully to make sure they put the hose in the right tank. This time I was lax, and... you guessed it. Oscar even handed me the filler cap, and it should have registered with me that it was bronze, not silver in color. By the time I realized it, several gallons of aqua Pago had been injected into my fuel supply. Luckily, it was in the day tank, not the main tank, and we could wait until it settled to the bottom, then drain it off in the engine room. Even before Ian arrived, we had that task complete. Or so we thought. (foreshadowing)

We waited for Ian's late-night landing with much anticipation. I knew he was the the person to help alleviate our endless engine problems. Handy with a wrench, Ian takes the attitude that there's nothing he can't fix. He's just the kind of guy you need on a boat. But I was getting worried as we watched the passengers emerge from customs and into the waiting throng. No Ian. We waited and waited. Finally, he showed his face. Boy, was I relieved. The next day, he quickly scoped out our engine problem -- hydraulic lock. There was water in the pistons, making them unable to move up and down. He stripped off the injectors, we turned her over a few times, and all sorts of stuff came out the cylinders. How it got in there, we still don't know. Most seem to think it was a wave that traveled forward up the exhaust system, but it's a long way. I wonder.... Anyway, the Volvo roared to life again under Ian's supervision, and we made our way off the concrete customs dock onto one of the huge mooring buoys in the harbor, which we had to share with two other sailboats.

We were beginning to realize that everything we had heard about Pago was true. It was rainy, dirty, smelly and noisy. The jutting "Rainmaker" peak attracted every rain cloud in he area, and they provided an almost constant downpour. The harbor was foul with sewage and waste from the nearby tuna cannery, which smelled of decaying fish. The diesel generating plant next door set up a level of noise that made normal conversation impractical. The only saving grace was the shopping. Not only were the liquor prices, as mentioned, the lowest in the Pacific, but they had a Caustic! Well, not really a Caustic -- it was called Cost-U-Less, and it was a reasonable imitation. Containers full of U.S. goods made their way onto the shelves to be scooped up by grateful Samoans (and Tongans, as we recalled from our time there). We provisioned like we hadn't been able to since Mexico.

The mechanical problems began to mount, however. Every time we had one thing fixed, two more would malfunction in the sweltering heat. We traipsed around Pago endlessly in search of parts, riding the lavishly-decorated trucks that blared the Macarena from their boom-box stereos. Finally, with Ian's help, we were ready to go. We started the engine, let go our mooring and headed for the customs dock, where we were going to take on some more water. For some reason, she didn't feel right as I guided her into the dock, and when I went to put her in reverse I knew something was wrong, as our progress was unslowed and we hit the dock with another loud thud. Heading below to pull up the floor boards, we saw that the motor mounts holding the propellor shaft coupling to the engine transmission had sheared off. I had to scratch my head at that one. It must have been the time in Tonga when we ran over the mooring line. We had been hanging on by a thread -- or maybe a rubber band since then.

But, have no fear, Ian was there. He quickly devised a solution, and we shopped the length and breadth of Pago -- again -- to find the materials he needed to implement it. The next day, the transmission was back together and we were back in business. Finally, we said goodbye to Pago. Motoring out through the entrance, the seas got bouncier the closer we got to the entrance buoy. Then, just as we approached, the engine sputtered and died. Quickly getting the sails up, we thanked goodness that we'd at least gotten out of the harbor. There wasn't much wind, so we just ghosted along while Ian went to the engine room to discover the problem. The fuel filters were plugged up with water, no doubt left over from the Oscar incident. It must have been hiding in the far corner, where we couldn't drain it because of the boat's natural starboard list and nose-down attitude from the weight of the stove and anchor chain. The bouncing up and down had mixed it with the diesel fuel, and the filters had separated it again, causing them to plug up. We were draining water from the filters regularly for many, many engine hours after that. Good old Oscar.

Hoping to make it to Christmas

Making steady progress northward in the southeasterly trades, we tried

to sail as close to the wind as we could because Hawaii was about 20 degrees

of longitude to the east, and I knew we would be lucky to keep our easting

once we encountered the northeasterlies above the equator. If the wind

shifted more to the east, we would have to tack back and forth, which could

be a time-consuming effort the way Markenurh goes to windward. But

our luck held and we were even able to crack off on a beam reach one day

when the wind switched more to the south. After a couple of weeks, the

long, low outline of Christmas Island appeared on the horizon. Part of

the scattered island nation of Kiribati, Christmas Island is actually spelled

Kiritimati in the native language. But they pronounce the letter combination

"ti" as "ss." Thus the name of their country is pronounced "Kiribass."

Making steady progress northward in the southeasterly trades, we tried

to sail as close to the wind as we could because Hawaii was about 20 degrees

of longitude to the east, and I knew we would be lucky to keep our easting

once we encountered the northeasterlies above the equator. If the wind

shifted more to the east, we would have to tack back and forth, which could

be a time-consuming effort the way Markenurh goes to windward. But

our luck held and we were even able to crack off on a beam reach one day

when the wind switched more to the south. After a couple of weeks, the

long, low outline of Christmas Island appeared on the horizon. Part of

the scattered island nation of Kiribati, Christmas Island is actually spelled

Kiritimati in the native language. But they pronounce the letter combination

"ti" as "ss." Thus the name of their country is pronounced "Kiribass."

The lagoon at Christmas is too shallow to enter, so boats anchor in the rolly lee of the island. There was another boat anchored there when we arrived, so we asked them what the check-in procedure was. They said I had to go ashore and ferry the various officials -- agriculture, immigration and customs -- out to the boat by dinghy. My poor dinghy was in a sad shape by this time, with several holes in the rubber floor requiring constant bailing. I motored ashore and reported to the authorities. Soon, the team of officials necessary to clear us into the country assembled on the dock. Like most South Pacific islanders, the natives at Christmas Island are large people. The four of us in my dinghy brought the water pouring in even faster than usual, and soon after I had instructed them how to use the bailer and headed out to sea, the official in charge ordered me to turn around and head back to the dock. Deeming my leaky craft unseaworthy, he decided I should take only one official at a time. That lade for a full day's work, but eventually we had the paperwork completed and the crew could go ashore and look around. There wasn't much to see, however, and we only stayed a few days. Our last day, unfortunately, the dinghy was left too long on the beach and practically wrecked by the encroaching surf. We lost a floorboard and the floor was now ripped half off. Ian did a quick fix, though, sewing it back onto the lifelines in anticipation of a lobster dinner ashore that night which proved a big disappointment. The next day we were off for Hawaii!

One of the amusements engaged in by the crew to

make the passage more interesting is wagering on just when we would make

landfall. The passage from Samoa to Kiritimati had been slow, averaging

less than 100 miles a day, so Ian and Oscar were guessing it would take

another two weeks to cover the almost 1,400 miles to the Big Island. I

knew, however, that once we got into the steady northeasterly trades we

would begin to move more quickly than in the doldrums around the equator.

Sure enough, our progress picked up and 10 days later we could see the

high volcanic outline of Hawaii. A close encounter with an inattentive

fishing boat off the south coast woke everybody up in a hurry, and soon

after that we ran out of wind. We were in the huge wind shadow of the Big

Island with 30 miles to go. My engine (Old Reliable) did the rest, however,

and with the aid of a helpful Coast Guard Auxiliary radio operator, we

secured a berth in Honokohau Harbor, tied to some lava rocks. I quickly

made arrangements to have the boat hauled by Gentry's Kona Marina and put

in their storage yard while I booked a flight to Ohio. Ian already had

a ticket, but had to book a flight time, while Oscar planned to tour the

islands a bit before heading on to Vancouver. I had by then decided against

attempting to sail onward for home, having had more than enough sailing

to last me a lifetime. I wanted to hedge my bets by keeping Markenurh

in the tropics, where I could easily head south again if returning to school

proved not to my liking. Soon I was in Ohio and another world.

Read Part IV